👋 Hoi, Ed & Chris hier. In de Atlas van het Lange Nu duiden we onze snel veranderende wereld. We doen dit met de historisch-futuristische bril van de langetermijndenker en de gereedschapskist van de speculatieve maker. Door het verleden te duiden openbaren zich immers nieuwe verbeeldingen van de toekomst.

🥳 For our more international audience who’ve been putting our newsletters through Google translate, or for those wanting to forward our newsletter to friends, students and colleagues who don’t read Dutch, we have good news! — We’ve started an English edition over at Substack titled Atlas of The Long Now. There we are publishing translations within a week after we’ve sent out the Dutch edition, and we’re translating some popular previous issues this fall. You can subscribe here.

En nog wat meer goed nieuws. Het afgelopen jaar hebben we uitgebreid geschreven over de toekomst van vertrouwen, en de grote rol die vertrouwen speelt in het mogelijk maken van complexe moderne samenlevingen. Pakhuis de Zwijger vroeg ons in het kader van hun Designing Cities for All Fellowship (DCFA) ons Toekomst van Vertrouwen-dossier dit najaar verder uit te werken. In gesprekken met verschillende experts willen we uiteenlopende aspecten van dit thema verder uitdiepen. We gaan deze gesprekken inleiden met, hoe kan het ook anders, een historische duiding van hoe vertrouwen de afgelopen duizend jaar gestalte kreeg, en een aantal ontwerpprincipes en toekomstscenario’s die laten zien hoe vertrouwen georganiseerd en geborgd zou kunnen worden in de toekomst.

Als een soort schot voor de boeg hebben we voor ons internationale panel van experts dan ook een inleidend essay geschreven dat we hieronder graag met jullie delen.

De komende tijd zullen we meer informatie geven rondom de verschillende elementen van het programma en welke gasten we zullen hebben. Er komt een podcast, een boekenclub en een aantal events bij Pakhuis de Zwijger waar live en online aan deelgenomen kan worden. Om te beginnen maar even een kort een rijtje data voor in de agenda:

- Maandag 3 oktober 20u-22u — De DCFA launch: De introductie van de Chrononauten en ons onderwerp; Architectures of Trust.

- Maandag 7 november 20u-22u — Building a Public Domain: Over hoe we in het publieke discours tot een gedeelde waarheid komen.

- Maandag 14 november 20u-22u — Building a Public Culture: Over onze digitale identiteit, van wie die is, en hoe die bepaalt hoe we invulling geven aan ons burgerschap.

- Maandag 21 november 20u-22u — Building a Public Governance: Over hoe nieuwe digitale infrastructuur een rol kan spelen in het bouwen van een participatieve democratie.

Dan nu, without further ado, ons essay.

Building Trust in the Electric Age

‘Every kind of peaceful cooperation among men is primarily based on mutual trust and only secondarily on institutions such as courts of justice and police.’ —Albert Einstein

In November 17, 02021, a US court sentenced Jacob Chansely, also known as the ‘QAnon Shaman’, to 41 months in prison for his role in storming of the US Capitol on January 6, 2020. Images of Chansley in the Capitol building went viral because of his ‘barbaric’ outfit. His painted face, the large spear he carried, and his horned fur hat became symbolic for the mayhem that day. Because of this, Chansely’s sentence was extra harsh. To set an example among the wild online tribes that stormed the Capitol. According to the judge who sentenced him Chansely frequently posted ‘vitriolic messages on social media, encouraging his thousands of followers to expose corrupt politicians, to ID the traitors in the government, to halt their agenda, to stop the steal, and end the deep state’ prior to his storming of the Capitol.

The story of Jacob Chansely and the events on January 6th became emblematic of a sharp deterioration of societal trust in Western societies during the last 30 years. The social media messages of Chansely are testimony of a widening and deepening social mistrust in our democratic and governmental institutions and the officials, professionals and experts that make it run. This lack of trust is, of course, deeply problematic. Especially for democratic communities. If we don’t address and fix this trust-problem, it will spell the end of our way of life.

Trust is the glue that holds societies and civilizations together. It’s the core principle on which all human relationships are build. It is consequently also the most sacred principle of effective communication. It is quite remarkable, in that light, that the societal dynamics of trust are still poorly understood. Especially when one considers it has been over thirty years since the introduction of the most omnipresent communication-platform ever conceived; the Internet. It is time that we start exploring how societal trust works, how it is produced, and how it is linked to communication technology. If we know it’s dynamics, we can perhaps design our way out of our current predicament.

There is a link between societal trust, information technology, the experience of community and the scale of human cooperation that a particular society is capable of. To understand this link, it is helpful to take a few steps back, zoom out, and look at the introduction of the printing press in the mid 1400’s and how it transformed society and made the Modern world possible.

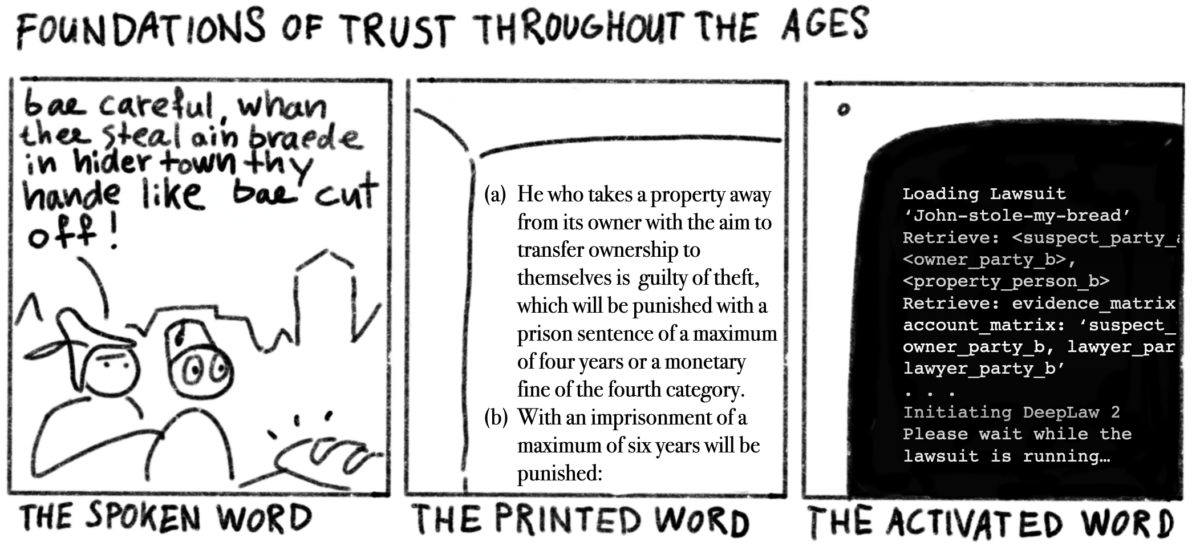

Before the invention of the printing press the dominant information technology in Europe was the spoken word. This had obvious limitations. We had to meet each other, so we could talk to each other, so we could build trust, so we could cooperate effectively. Trust was a very personal affair. The institutions of trust where small villages, family structures, friendships, clans, and fealty. Within these institutions cooperation and division of labor could take place. Something that was quite challenging outside these circles of trust. This dependence on spoken word made large communities and economies of scale almost impossible.

With the invention of the printing press, and the subsequent proliferation of publishing houses, Europe was introduced to a powerful new information technology – the printed word. The mass production of information that became possible allowed communities of trust to grow beyond the circle of personal acquaintance. Trust became a more abstract experience. People started to rely on the printed word – on schoolbooks, banknotes, newspapers, lawbooks, land maps and nautical charts. The new architecture of trust was built on the objectivity of experts, professionals and their bureaucracies that were associated with the production of this more abstract level of trust. The printing press thus made information scalable, which made trust scalable, which made the sense of community scalable, which made cooperation scalable.

In the nineteenth and twentieth century we were introduced to another information technology; electronics. Which subsequently led to new methods of communication – telegraph, radio, telephone, television, and the omnipresent personal computer of today. Especially after the introduction of the World Wide Web and other Internet applications the dominant medium of trust shifted again. Although the spoken word and the printed word are still around, and have their place in society, the dominant information technology became the activated word. (We call it ‘the activated word’ because computer code does not need humans to get work done; think robotics and machine learning.) But, while the dominant medium shifted from the printing press towards the new electronic realm there are, as of yet, no new architectures of trust in place to imbue its users with an even more abstract level of trust – an absence that undermines our sense of community and, if we don’t fix it soon, our ability to cooperate.

If we want to learn anything from this very brief history of trust, we need some sort of formula (or taxonomy, or definition) that establishes the social mechanics of trust. Because only if we know its mechanics, we can draw up design principles for producing trust in the electronic age.

So, to move forward, we think that we can safely define the social space where the linking of societal trust, information technology, sense of community and the scale of human cooperation happens as a public sphere. And to put it all into a single definition:

A public sphere produces public trust by imbuing information technology with a measure of objectivity – a notion of truth that is independent from human subjectivity. This measure of objectivity is called the architecture of trust. It enables the alignment of individual norms, identities, and interests into a sense of common ownership which provides the safety needed for people to cooperate.

Looking back with this formula in mind it makes sense that in the age of the spoken word people tried, by getting to know each other, to establish some measure of objectivity. By knowing each other’s subjectivities, one could, with some human insight, perhaps deduce some objective truth. That this is difficult speaks from the fact that these people lived in a very subjective universe. Their world view was very magical. Their world was mysteriously animated or otherwise divinely inspired.

When the printed word entered the scene people slowly started to trust law books, banknotes, land maps, sea charts because they trusted the craftsmanship of the people (and their institutions) that produced these printed artifacts. From this trusted craftsmanship slowly there emerged the notion of professionalism. Professionalism is a work ethic that encourages workers to leave their subjectivity at home and become an objective ‘cog in the machine’. We trust our doctors, lawyers, bookkeepers, politicians, mapmakers, teachers because we trust their objectivity. Professionalism was the architecture of trust in the age of the printed word, and bureaucracies were its scaled-up institutions.

Jacob Chansely’s ranting about corrupt politicians and the deep state make much more sense now. Professionalism was the architecture of trust that worked in the printed age. With the advent of a new information technology, the activated word, our faith in human professionalism is waning. Our (subjective) faith in the objectivity of experts and professionals does not cut it anymore. We need something stronger, something more objective. We need an architecture of trust that can withstand the massive challenges of the activated word.

We live in a transitional moment. We are still governed by the institutions that emerged in the age of the printed word, but most of our information and communication takes place in the realm of the activated word. This is a fraught situation because the dynamics of the printed age are different than those of the electronic age.

Here are a couple of those differences:

- The electronic realm processes much, much, and much more information than the printed realm.

- In contrast to the printed realm, the electronic realm does not only distribute information but also produces it.

- Because it is activated the electronic realm can control the robotic workings of critical infrastructure.

- In the electronic realm everybody is a producer of information, which is different from the printed realm that was controlled by an elite cadre of professionals.

- The electronic realm makes society much more transparent because everybody can disclose information in it. There is no ballotage of professional editors, curators, and publishers.

- Compared with the printed realm the electronic realm is a ridiculously complex and abstract place. It is built and governed in the language of higher mathematics, which makes its inner workings inaccessible to most.

We thus need to design a new architecture of trust that fortifies a much higher level of objectivity within the activated word, so that it can produce public trust, on which new (more democratic) communities and new (more democratic) ways of human cooperation can be established.

This is not something that must be done overnight. Because the stakes are high. Like professionalism became the foundation for our current representative democracy—where a buffer of professional politicians had our backs—and the many professional bureaucracies (corporate, governmental, or otherwise) that ensure accountability and durability, this new architecture of trust will become the foundation for our future society. Thinking about the future of trust is key to the establishment of an inclusive and sustainable way of life.

Fijn weekend, en tot de volgende editie.

Liefs, Ed & Chris

Here are a couple of those differences (and why they are dangerous)

1. The electronic realm processes much, much, and much more information than the printed realm.

P: It mainly produces an overload of redundant rubbish. The problem with the digital realm is that it does not distinguish (anymore) useless or even wrong information from the useful and correct (there are of course exceptions, like Wikipedia, old school websites (edited) etc, but the digital realm has mainly exacerbated the phenomenon of fake news.

2. In contrast to the printed realm, the electronic realm does not only distribute information but also produces it.

P: Give me one example of the production of useful and/or correct information by the digital that cannot or is not produced by more traditional media.

3. Because it is activated the electronic realm can control the robotic workings of critical infrastructure.

P: Who writes the program / the algorithm? In the digital realm the author of the algorithm is the one in control (whether they be a singular person or an anonymous group). Unlike the physical ruler, whether he/she is chosen democratically or whether a self-appointed autocrat, is at least visible (and can be attacked, send away or killed). In the digital realm such ‘rulers’ are – often deliberately – hidden and mostly unaccountable.

4. In the electronic realm everybody is a producer of information, which is different from the printed realm that was controlled by an elite cadre of professionals.

P: Yes, that is what we hoped for in de dinosaur-years of the digital. How wrong we were (how wrong we have been proved to be).

5. The electronic realm makes society much more transparent because everybody can disclose information in it. There is no ballotage of professional editors, curators, and publishers.

P: Yes, and that’s the problem isn’t it: without some sort of control (of the information) anybody can upload shit adding to the already overload of undistinguished information.

6. Compared with the printed realm the electronic realm is a ridiculously complex and abstract place. It is built and governed in the language of higher mathematics, which makes its inner workings inaccessible to most.

P: See comment point 5

We thus need to design a new architecture of trust that fortifies a much higher level of objectivity within the activated word, so that it can produce public trust, on which new (more democratic) communities and new (more democratic) ways of human cooperation can be established.

P: True, we need to build a new system of trust, but I am very, very distrustful of the digital being the solution to that. It is inherently messy and controlled by hidden forces much more powerful and unaccountable that the – also messy, but at least visible – physical realm.

Besides, I would sooner trust a panel of experts (for instance the editors of a physical newspaper) – however anarchistic my personal convictions may be – than the anonymous expertise of an algorithm or the populist opinions of ‘the people’(like nowadays, farmers, ‘wappies’, and the like)

Hi Piet, good points. Agree on all of them.

It is understandable and prudent to distrust any solution of trust that emerges from the digital. But we also feel it is prudent to research one.

In case we don’t find anything that can stand the test of our (and your) watchful and distrustful eyes – a real possibility – we at least know what to point at if others may try.

That said, we begin with a hopeful attitude. We feel it is good to remember that the ‘older’ ways weren’t very shiny, to begin with.

Editorial boards, bureaucracies, the professionals that supported them; all operated in very flawed ways from a trust standpoint. Perhaps we didn’t notice as much because they were also very untransparent. Or, perhaps we just accepted it by default.

Keep you posted!

On point 2: In my opinion Bellingcat is an interesting example of open source and transparant (citizen) journalism, which is very much enabled by, if not almost inconceivable without, the digital. But also practices like Forensic Architecture, and other open source intelligence (OSINT) practices come to mind.