Hope and Fear of a Futurist

+ AI-hersenscan en Synthbiotisch samenleven.

Goedemorgen allemaal!

Vandaag delen we Christiaans stuk ‘Hope and Fear of a Futurist’ (in het Engels). Het is een kort essay waarin hij reflecteert op wat het betekent om met de toekomst bezig te zijn in onze huidige turbulente, ingewikkelde tijd. Hij schreef het op uitnodiging van het Russische underground kunstcollectief Lepista Nuda en het werd als Russisch gedicht gepubliceerd in hun zine Chifan.

Verder twee AI-overdenkingen:

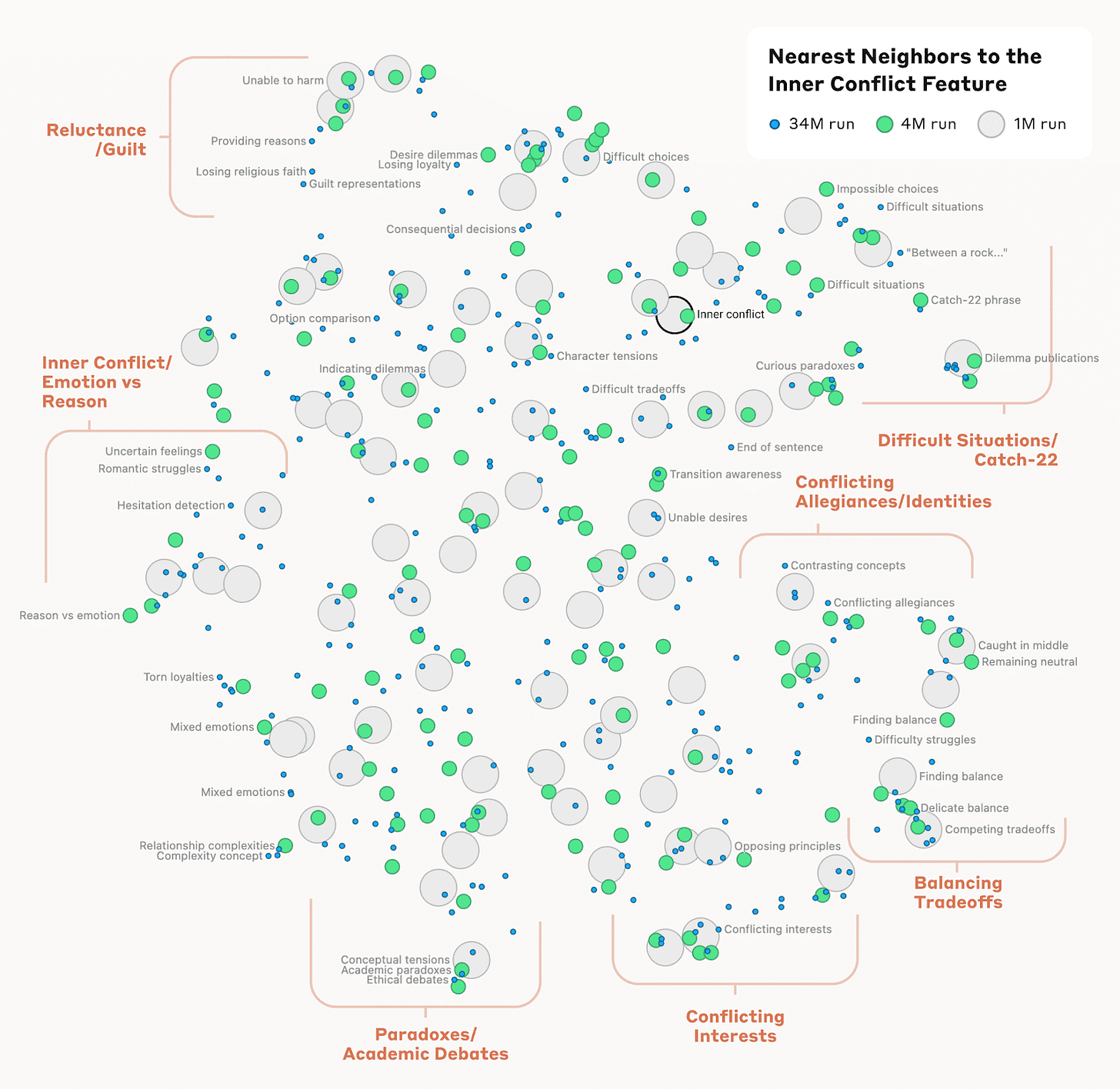

Hoe een AI-hersenscan het mensenbrein een spiegel voorhoudt — AI-bedrijf Anthropic heeft een methode ontwikkeld waardoor het in een AI-zwarte-doos kan kijken en kan zien welke ‘neuronen’ in het AI-model geassocieerd worden met welke concepten, vergelijkbaar met een hersenscan. Maar wat vertelt ons dit?

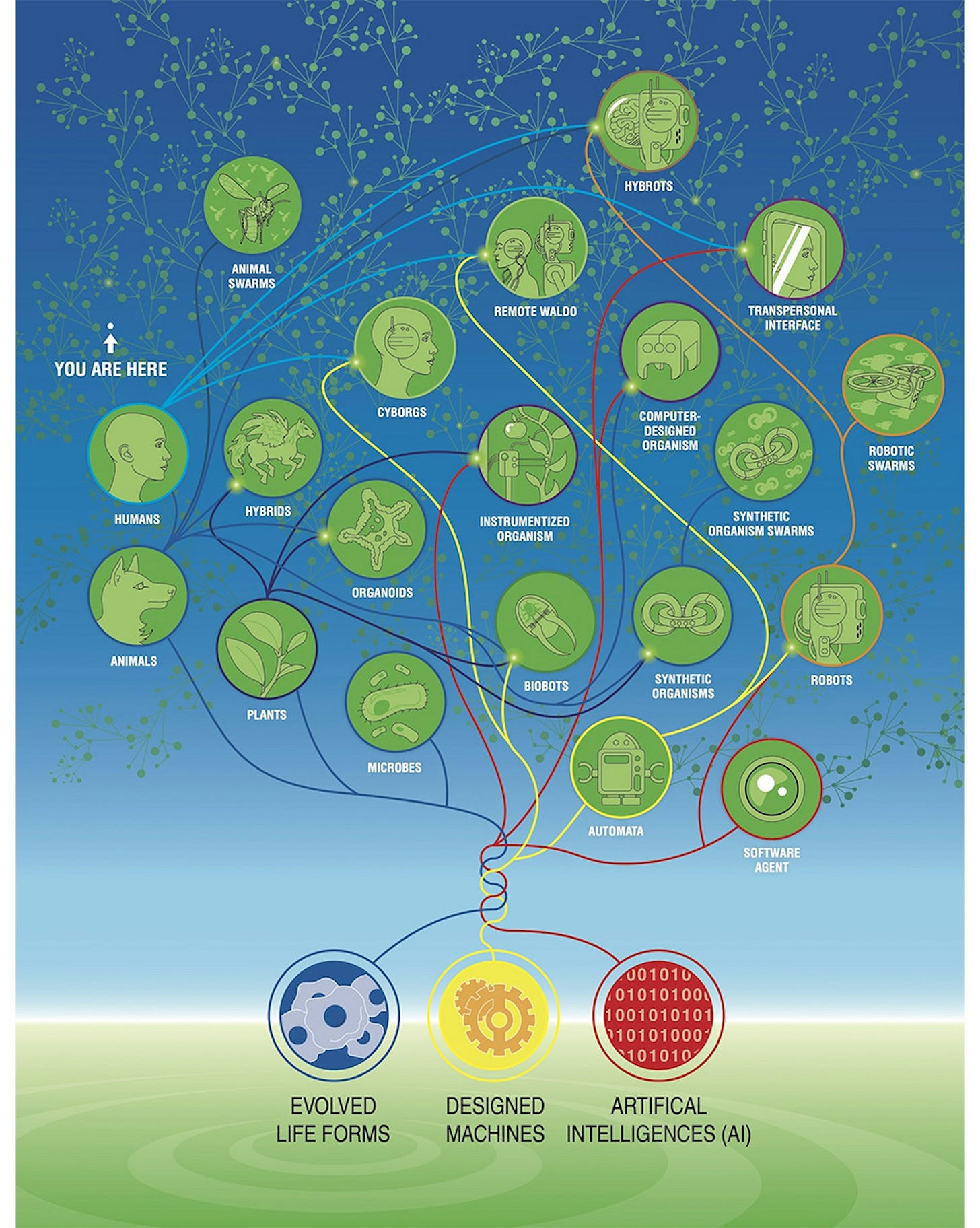

Synthbiotische samenleven — Biologieprofessor Michael Levin stelt dat de tegenstelling kunstmatige versus natuurlijke intelligentie weinig behulpzaam is in het begrijpen hoe intelligentie werkt. Intelligentie is volgens hem inherent een collectivistisch fenomeen. Maar wat betekent dit nu AI een integraal onderdeel van onze samenleving aan het worden is?

Hope and Fear of a Futurist

As a person who makes a living identifying and interpreting historical shifts, and extrapolating these shifts into futuristic scenarios, there is a lot out there that gives me hope. But, equally true, there is also a lot out there that scares me breathless.

I can say with confidence, looking at the big picture, that I think humanity is on a trajectory towards a more wholesome place. This gives me great hope. I can also say that there is a reasonable chance that this trajectory will not run its course.

The window of opportunity for nature-inclusive policies and practices is closing fast. Which is alarming to me, to say the least. And then there is all the misery and awfulness that human beings keep inflicting on their fellows, on ever larger scales. Which regularly fills me with fear, loathing, and sadness. The weight of the world can be heavy. It can induce the feeling that all hope, is a fool’s hope. You can call me a fool.

I consider myself, in my core, as a deeply hopeful person. Why? I’m not quite sure. I think it’s partly because I’m an entrepreneur at heart. Not in the capitalist sense, but in the sense that I like to do things. I like to create things. I like to leave the world behind in a better state than I found it. And you cannot do this when you don’t run on the premise that a good outcome is possible. Hope is implicit for an entrepreneur.

The other reason, I suspect, for me being a hopeful person, is that I’m surrounded by loved ones. And love, in my experience, seems to be a force for deep healing. Deeper than the world we live in. Love infuses me with the feeling that even when all things fail and go to shit – on a deep, deep level, things are still OK. There is an infinite well of trust in me. Again, call me a fool.

Let’s consider these two personal engines of hope then.

On a more superficial, earthly level, I’ve always been someone who has taken his academic and aesthetic interests to the road. I never found myself a good match with the bureaucratic flow of academia, governments, and corporates. I’ve also never found myself attracted to the subsidized business models of the cultural world. I just like to do things my way. Not because I’m particularly judgmental towards other ways (to each their own). I just enjoy creating (or discovering) new ways, new path, new corridors. Sometimes they lead somewhere interesting, other times they are dead ends. But all my endeavors and adventures are fueled by hope. And for Studio Monnik, the creative thinktank for historic-futuristic research practice that I co-founded, hope is its reason d’etre.

In 2011 Edwin Gardner and myself found ourselves baking pancakes at Occupy Wall Street. We were sympathetic to its objectives, but we were also a bothered by the fact that the movement could only formulate what it was against. There was no imagination of the better world we said we fought for. A creative and intellectual deficiency expressed pointedly by Slavoj Žižek when he quoted Fredric Jameson, who said; ‘it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism’.

Because we had nothing better to do at the time – we were both in-between projects – we decided to have a go at it: we decided to search for a substantiated imagination of a sustainable, inclusive, and adventurous society. A project that developed into our current futurism practice.

We were not completely naive. We knew that it was a ridiculous quest with small changes of success. But we just figured; who knows, perhaps just pursuing these kinds of questions would lead us somewhere interesting and unexpected.

Which it did, entirely. 13 years later it led us to a new understanding of the society we live in and the futures that are possible for us. It also led to the development of many fun and creative ways in which we can share our futuristic insights. Insights that, we’re happy to notice, generate not only strategic awareness and insight (what people pay us for) but also hope. Hope that there are possible futures out there that work for all of us. Hope that there are always possibilities that lie beyond the status quo.

But there’s a deeper source of hope, for me.

On a personal level, I’m filled with a deep sense of love and wonder. I have no rationalization of these feelings. They are just part of me. And if there is a true source of the fool’s hope I carry, it probably lies within these feelings. The love I feel every day for my friends, my partner in life, and our daughter tells me that there is a bottomless well of goodness somewhere. That – hidden, out of sight, below the everyday surface of things – there is a warm embrace that connects all. I’m not a religious man at all, but I do understand the sort of trust that says, ‘even if everything goes wrong and the worst things imaginable happen, on a deeper level, things are still OK’.

I admit that this is not a proposition that is tested to its limits. At least not with me. (And let’s hope it stays that way.) Also, it’s a feeling that sometimes escapes me. But it’s there, more often than not. Especially now I get older. But the moments I don’t have access to this bottomless pool of trust, those are the moments I fear the most. Because this severed connection, this isolation, creates the space where despair flowers. And despair is a ruthless heartbreaker. And without a heart, what is left of us? Nothing but dust.

For me hope emerges from love and taking action – from doing things for the benefit of all. And what I’m scarred of is the absence of these two things, the vacuum we call despair and passivity.

🖤

Christiaan Fruneaux (Amsterdam, 11 March, 2024)

Hoe een AI-hersenscan het mensenbrein een spiegel voorhoudt

Een van de grote vraagstukken van AI is het zogenaamde Black Box probleem. AI reageert met antwoorden, beelden of audio op onze vragen, maar computerprogrammeurs hebben geen idee hoe dat precies in zijn werk gaat. De AI is als het ware een magische doos. Als je erin kijkt, zie je een Large Language Model (LLM): bergen statische verbanden in een soort multidimensionale matrix van cijfermatige waarden die ons op zichzelf niets zeggen. Deze waarden zijn het resultaat van bergen aan verwerkte data, maar is verder niet interpretabel.

Hier is nu verandering in gekomen. AI-startup Anthropic heeft een soort digitale hersenscan voor AI’s ontwikkeld die kijkt welke delen van een LLM oplichten wanneer die geconfronteerd wordt met specifieke concepten. Vergelijkbaar met hoe een hersenscan kan laten zien welke neuronen in je brein oplichten wanneer je aan een appel, liefdesverdriet of bepaalde muziek denkt.

Deze digitale AI-hersenscan draait terwijl de AI tot een antwoord komt, en geeft dus inzicht in hoe de AI door een soort semantisch web van concepten en hun associaties beweegt. Je kan deze scan ook andersom gebruiken. Als je weet waar in de LLM bepaalde concepten zitten, kunnen ze ook onderdrukt of versterkt worden.

In een voorbeeld werd het concept ‘The Golden Gate Bridge’ versterkt. Als je dan aan de AI vroeg wat het was, dan antwoordde het niet ‘ik ben een AI’, wat het normaliter zou doen, maar zei het dat het de Golden Gate Bridge was.

Hoewel dit een belangrijke stap is in de AI-ontwikkeling en vooral het bestuurbaarder, veiliger en transparanter maken van AI’s, is het de vraag of deze digitale hersenscans ons echt inzicht geven in hoe AI’s denken.

Het afvuren van een set neuronen, in een kunstmatig of biologisch brein, toont dan misschien wel waar een concept in een brein zit en hoe het verbonden is met andere concepten, maar wat zegt dit over hoe we denken?

Onze gedachtewereld bestaat uit meer dan het navigeren van een semantisch web. Het bouwen van argumenten, het vertellen van verhalen en het reflecteren op een ervaring is diep verweven met onze emoties, intenties en ervaringen.

Wat misschien nog wel het interessantst is aan het onderzoeken hoe een AI denkt, is wat het te vertellen heeft over hoe wij zelf denken, en wat de waarde van onze gedachten en ons bestaan is.

Als een AI kan wat wij kunnen, maar dan zonder bewustzijn en zonder ervaring, dan verschuift onze kijk op ons eigen brein misschien wel van denkgereedschap naar bewustzijnsantenne. Een orgaan dat ons gewaar maakt van onszelf, de ander en onze plek in het universum.

Synthbiotische samenleven

Volgens biologieprofessor Michael Levin slaat veel van het discours rond AI de plank mis omdat het blijft hangen in de tegenstelling mens versus machine, natuurlijk versus kunstmatig. In een uitgebreid essay legt hij uit dat het zinniger is om een vloeibaarder en diverser idee over intelligentie te hanteren. Een spectrum waarin biologische en technologische vormen van cognitie naast elkaar bestaan met onderlinge kruisbestuiving. Hij noemt dit synthbiosis, een netwerk van relaties en interacties tussen natuurlijke en kunstmatige intelligenties die elkaar kunnen aanvullen en verrijken.

Want, zo stelt hij, de biologie zelf laat immers zien dat intelligentie, perceptie en bewustzijn samen een spectrum vormen. Zo is er miljarden jaren geleden bijvoorbeeld vanuit dode materie leven ontstaan, leven dat eerst simpel en eencellig was, maar dat uiteindelijk door evolueerde tot complexe organismen zoals wij. En deze mini-evolutie herhaalt zich telkens weer wanneer er een enkel eitje bevrucht wordt en er een compleet mens uit kan ontstaan.

Dit continuüm van simpele tot complexe vormen van intelligentie en bewustzijn bestaat niet enkel in de tijd, onze eigen intelligentie, die we elke dag ervaren, is samengesteld uit vele autonome intelligenties waar we ons niet bewust van zijn. Elke individuele cel bezit namelijk een vorm van perceptie en handelen, en samengesteld in collectieven vormen deze cellen organen die vervolgens ook weer weten wat ze als orgaan moeten doen. Dit doen ze volledig autonoom, zonder dat we ook maar een gedachte wijden aan het kloppend houden van ons hart, en het verteren van ons eten.

Van deze onderliggende vormen van intelligentie zijn wij ons over het algemeen niet bewust (op een aantal goed getrainde boeddhistische monniken na wellicht). Maar ze zijn essentieel om in leven te blijven, emoties te voelen en te kunnen luisteren naar ons lichaam (introceptie).

Dat ons bewustzijn gedragen wordt door de vele samenwerkende collectieve intelligenties van ons lichaam, is een gedachte waar de meeste mensen niet zoveel moeite mee hebben. Het lichaam is niet simpelweg een stuk gereedschap dat het brein gehoorzaamt, hoewel we dat soms misschien graag zouden willen. Je hebt immers geen directe controle over je darmen, over de blos op je wangen, en over hoelang je herstel duurt als je ziek bent. Sterker nog, wat je wil wordt soms ingegeven door organen die doordrukken wat zij willen. Want wie heeft er eigenlijk trek in een hamburger? Jij of het microbiotisch collectief dat in jouw buikholte woont?

Maar als het op kunstmatige intelligentie aankomt, dan moet het zich toch vooral gedragen als gereedschap. Passief, gehoorzaam en als een verlengstuk van onze wilskracht. Maar zo gedraagt AI zich natuurlijk niet, het werkt met ons samen, net zoals de intelligenties in ons lichaam.

Levin schrijft:

If someone uses an AI to make something, for example, who really created it? The AI? The person using the AI? The people who made the AI? The people who made the works the AI was trained on?

The confusion comes from trying to maintain a binary distinction between creators, tools, assistants and teachers.

AI is een synthese van kennis, van de patronen in onze taal, beelden en data, en we werken met AI door er (letterlijk) mee in gesprek te gaan. AI is het resultaat van collectieve intelligentie, en zo zouden we er ook mee om moeten gaan.

Het nieuwe en confronterende van AI is dat het onze plek in de intelligentiehiërarchie bevraagt. Over het algemeen zien we onze intelligentie en ons bewustzijn als iets unieks en diep persoonlijks. Iets waar we mee geboren zijn, waar we hard aan gewerkt hebben op school, en waarmee we ons kunnen onderscheiden van anderen.

We gaan een toekomst tegemoet waarin het onduidelijker wordt waar de een z’n intelligentie begint en die van een (technologische of biologische) ander ophoudt. Intelligentie wordt zo in zekere zin steeds collectiever.

Zo’n soort toekomst vereist nieuwe instituties en een nieuwe infrastructuur om dat in goede banen te leiden. Uiteraard zien we hier ook weer een rol voor ons geliefde Universal Data Commons scenario.

Dat was het voor deze week! Tot de volgende.

Liefs 🖖 Edwin & Christiaan